In the Western-half of Australia#

By

Heinz Dreher, April - May 2016

A major focus early in the year was a trip into the Centre and Northwest and had been in the planning for in excess of 12 months. My good friend Ruth Göttlicher had wanted to make another trip in the Australian Outback, her first having been in the 1970s, so I planned on this being the initial serious trip for the newly acquired camping buggy, having previously travelled with tents or swags.

In and Around the Western-half with Ruth Göttlicher#

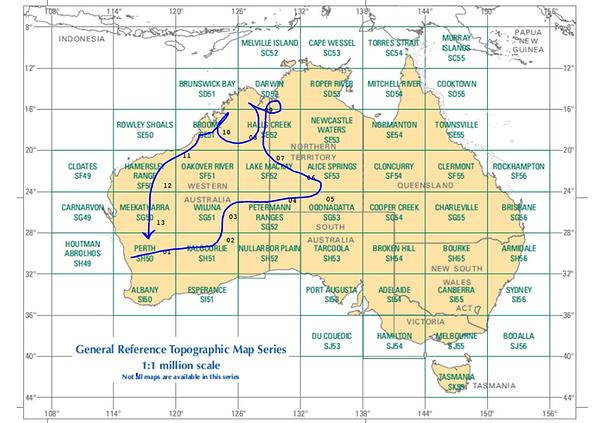

Ruth Göttlicher ventured from her Austrian hometown Vienna to experience some more Australian Outback travel that she loves so much. We chose an anticlockwise circuit of the western half of Australia, with a start date that would have us in the Kimberley as soon as possible after the Wet.

In planning the trip we envisaged three parts; getting into the Centre; the Finke Gorge National Park and progressing toward the Kimberley; and thirdly, a major focus the NorthWest – Kimberley and Pilbara regions of Western Australia.

The first part was a quite straightforward run up into Central Australia via the Great Eastern Highway to Kalogoorlie, north to Laverton and then northeasterly via the Great Central Road. I have travelled this route many times now and always enjoy the journey, the camps, and the long periods where one can have deep thoughts, intensive chats with one’s co-traveller, listen to an eclectic selection of music compiled for the trip, and to experience and admire nature.

For these longish trips to be successful and enjoyable, quite some preparation is needed. Obviously one needs to get the ‘where’ and ‘when’ aspects sorted out, and Ruth Göttlicher was very keen to engage intensively. We exchanged routemaps and notes via email, and gradually progressed our plans over a 12-month period, meaning that there was a well understood expectation regarding timing, places, costs, opportunities, and risks.

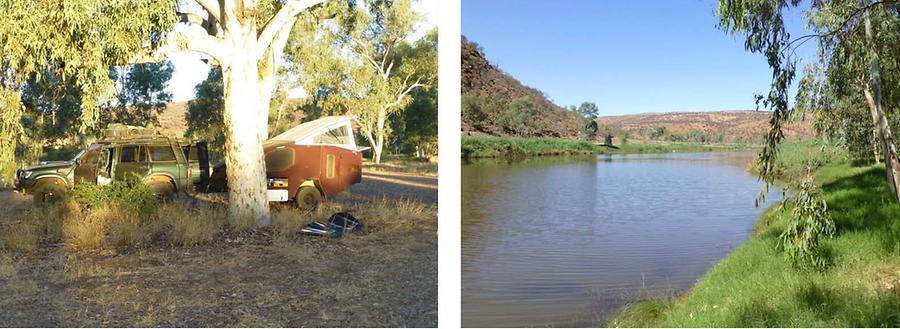

Also important is to have carefully assembled and well prepared equipment, and for this trip there was to be luxury camping accommodation in the form of the Vista RV XL Crossover (to give it its full name) and which I refer to as the camping ‘buggy’. During 2015, I concentrated on re-arranging my travel equipment and acquiring an outback travel trailer with all mod-cons. Camping with tent and/or swags can be quite exciting, but packing up camp is often a time consuming chore. Anyway, as one’s age advances it makes sense to simplify things -maximising the enjoyment whilst minimising the work effort to derive that enjoyment.

Camping buggy acquisition began with a November 2014 inspection trip to the factory in Bayswater/Melbourne/Victoria where my choice of buggy, the Vista RV is made. I liked what I saw – the factory, the methods, the people, and the product -and immediately ordered one. They make just 50 or so per year. It was to be ready after the circa six month build time, and so I collected it in June/July 2015. It will go anywhere the 4WD will go, but just like the 4WD, might not come back! Therefore, one must always plan ahead and be cognisant of possible consequences of one’s actions and decisions. So, there would be places my rig would go, but where i would choose not to go, except in an emergency -the most compelling reason after safety being to safeguard the relatively large investment one makes in this equipment – in my case it is now well into the six figures. The camping buggy (designed ideally for two persons) can be opened up and ready for use within minutes of stopping, say 2-5 minutes if one is in a hurry. If it is cold, there is a button that can be pressed to start the diesel space heater – pure luxury. Cooling is not so simple! Water is on tap and pumped out via 12volt pump from the water tanks. It is no higher or wider than the 4WD vehicle, and therefore it does not contain a kitchen inside – that is a roll-out unit accessible from outside, just like the typical camper trailer. There is no canvas to deploy or pack up, unless one chooses to erect a side or rear annexe. With the roof pushed up on an angle from the centre to the rear, even a very tall person can stand erect. It’s called a crossover, as it combines the convenience features of a caravan and the agility of a camper trailer. Perhaps the only thing I did not like about it as it emerged from the factory was the all white colour scheme.

The camping buggy in its new livery.

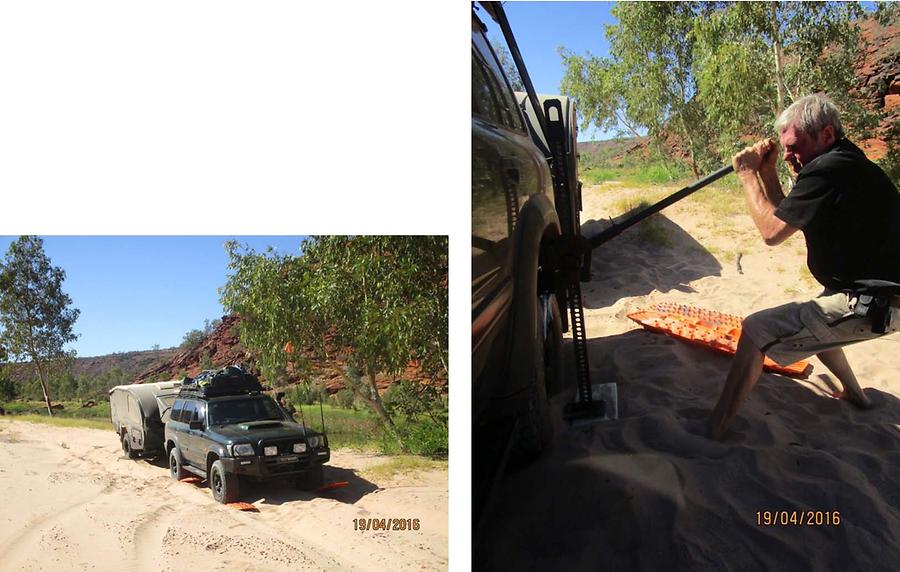

Additionally, one must have the will, resolve, and discipline to have a successful and stress free experience, and I am pleased to be able to report that in all the weeks (6 or 7 of them) and the thousands of kilometers (nearly 14,000), Ruth Göttlicher made every camp, every walk, and every social engagement with fellow travellers we met, an enjoyable and rewarding experience. She did not complain once! Now that is remarkable, and especially given that there were a few occasions where there would have been just cause – all due to errors or ‘bad’ behaviour on my part (e.g. deeply bogged in the soft sand of the Finke River-bed requiring a half-day extraction and recovery effort). I am very grateful for the mental preparation and discipline she showed, and which can be taken as an example for self-improvement – thanks Ruth Göttlicher.

Over the many outback trips I have now completed, there has emerged a set of heuristics that can act as a simple guide to enhance the bush camping experience. They are just rules-of-thumb and can easily be shared and learned for everybody to observe for mutual benefit. As improvements are found, by myself or co-travellers they are integrated into the H.h (Heinz’.heuristics).

Some campers don’t mind sand and dust in and on everything – that’s really simple to arrange! But in my case I prefer to have a clean camp and clean equipment, just as I like a clean house and home. Therefore I arrange for ‘clean zones – dirty zones’. Clearly there is going to be lots of dust, mud, … and other sources of ‘dirt’ when Outback, but this does not mean we need to have it in our beds, on our hands, and in our mouths – at least not all of the time! So, inside the buggy is a ‘clean-zone’, and to keep it that way one needs to manage the interface between ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’.

In picture Fig. 3 one can see the extent of the dust accumulating and swirling about the vehicles. None of this dust enters the camping buggy, and just a little enters the Nissan Patrol tow vehicle via the rear door-seals. This is by design, not by chance. And, quite obviously, if a person enters the buggy with shoes, and dirty ones at that, we eventually get the dirt into the bed, and elsewhere. Therefore, such an action is inconsistent with H.h.

Not all camps are in ‘dirty zones’ and our first stopover for the trip was in Kalogoorlie’s most pleasant public RV-park within walking distance of restaurants, shops, and as it happens, the famous brothels too. Picture Fig. 3 shows a clean zone. It was also most enjoyable because we met some rather friendly and helpful co-travellers.

Mahogany Creek (my home town) to Kalgoorlie is 600km. To Laverton via Leonora adds another 300km. Then on to the Olgas and Ayres Rock is another 1000km. Quite obviously this takes some days to traverse on unsealed roads and we enjoyed numerous camps, such as the one at Gill Pinnacle Fig. 4 and later at “Running Waters”, our first camp in the Northern Territory’s Finke Gorge National Park Fig. 4.

The Olgas, in the vicinity of AyresRock, are most spectacular, either as seen from afar, or from within … wouldn’t you agree? We camped in the bush outside the National Park controlled area, and were able to have our decent campfire and peace and quiet too. Uluru, as ‘they’ like it to be called these days – it’s Ayers Rock as I learned about it at school in the 1960s – is the second most popular tourist destination in Australia after Sydney, so one can imagine the resultant activity generated in the area: traffic; people; noise; litter; rules (to attempt to regulate and profit from the tourist onslaught); and many differing opinions on how one should ‘behave’ when in the area. Thankfully the Olgas, now mostly known as Kata Tjuta, are much less visited, and we were able to enjoy some wonderful walks

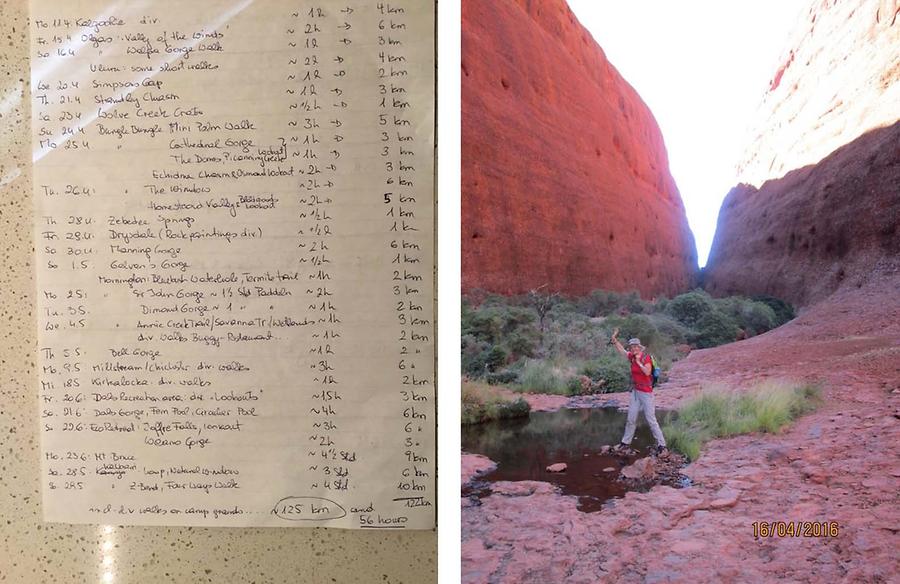

– the first of 30 or so treks/canoeing adventures covering more than 125km in track distance and logging three-score hours to complete – among just a handful of other visitors.

Ruth Göttlicher does lots of walking in Austria, and is expert in the management aspects of this activity. This is essential for safety, as one can appreciate beginning a 4-hour return trek at 2pm during the short daylight hours of our winter months is likely to result in problems. She can keep track of start times, relative progress, expected arrival at destination, and return times, and so help ensure the safety and enjoyment, without any fuss or bother, and very reliably. I did not realise how enjoyable these walks, some quite physically demanding, can be under such conditions. See Ruth Göttlicher’s track log in

And I think she enjoyed extracting the log from her daily journal as much as the walks themselves!

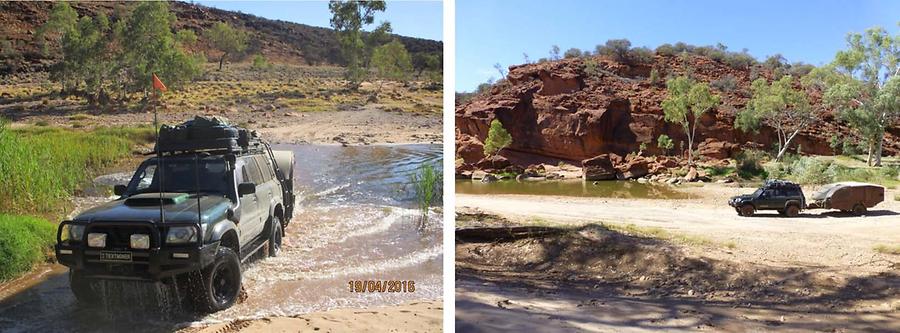

Well then, here we were in ‘The Centre’, and our first exciting extreme 4WD adventure was about to begin. The Finke River 4WD route is known for its demanding and changing conditions – and we were towing a 1700kg trailer too! Also, we approached from the south where most travellers proceed from the north. The predominant direction of travel can be understood by inspection of the maps of the area Fig. 7 in which one sees the relative proximity of Alice Springs from where many travellers begin their journey, and Hermannsburg, a place of some significance in the history of ‘black’ and ‘white’ affairs in Australia.

En route into the Finke Gorge National Park via the Palmer River valley we were flagged down by a carload of blackfellas who were most eager to show us their ‘friends’. The focus of attention was a rather large goanna, and at 2.5m one would think a possible threat, or a great meal, but it was quite content for us to approach within a couple of metres and take photos while it continued its ‘awkward’ gait across the barren landscape quite uninterested in our presence. Soon enough the sandy-earth terrain was replaced by rock at our first (of many) Finke River crossings, requiring careful negotiation so as to avoid underbody damage (e.g. fuel tank rupture), and damaged tyres/wheelrims.

There are questions from my friends: “why do you do these things, you know, travel in these remote and uninhabited places?” There is no simple answer, but part of it is most definitely the reward of arriving at a serene camp in nature, and with no (limited) intrusions from the ‘hordes of travellers’. Boggy Hole on the Finke River is an example. Despite it being so remote and difficult to access, we met two travelling parties – we all kept our distance (a respectful kilometer or so) and were able to appreciate our spaces. On the one hand it is rather reassuring to know that potential help is close by, but these same folks may be the source of considerable annoyance and intrusion (e.g. if they are using generators, or making boom-boom music, or doing motorbike activity) and liability (e.g. if they themselves are ill-prepared for outback travel and come to grief). But, look on the positive side – what a great camp at Boggy Hole! Of course we had a nice swim there, and appreciated the serenity.

With the ‘ups’ come the ‘downs’ – well, if one didn’t experience both one might never know what’s up and what’s down.

Naturally we needed to move on from our delightful Boggy Hole camp. And in this country, one usually crosses a river many times – each with different parameters. Our next Finke River crossing was a deep hole! We stripped off, walked and tested the depth and chose a path forward. It was but a momentary immersion into the 900mm deep water hole and all was ok.

In principle, the buggy goes anywhere the 4WD goes, but if one gets stuck – bogged, trapped in water,...-then its potentially a case of many thousands of dollars in recovery and/or repair costs, so I always err on the side of caution, and will not jeopardise my very considerable dollar-investment in equipment just to be able to claim ‘I went through 2m water’, for example. I seek enjoyment rather than macho-fulfillment.

All my gear needs to go wherever I choose is possible, with safety, security, and a minimum of fuss and bother. Oh, well, what a demand that is! There is circa 5 tonnes of vehicle and equipment when fully loaded and fuelled, and extending nearly 11 meters in length.

Naturally, sooner or later, a failure, mishap, or error occurs – the deep sandbog in the Finke River Gorge was due to an error on my part – higher tyre pressures for the rocky parts needed to be much, much lower for the soft sand parts, and I failed to recognise the extent of the deep sand section (too much haste, insufficient reconnaissance). This turned out to be a 3.5-hour extraction exercise, which in the end, was accomplished with outside help in just 20 minutes – thanks to the anonymous lone traveller who happened upon us. I was absolutely exhausted from the jacking and digging activity to advance just 4 metres in 3 hours. The helper had more maxtracks (bog tacks) that made eight in all between us, and that was the saviour – now I have ten maxtracks in my kit.

In the Outback one must be constantly monitoring and evaluating conditions. After the Boggy Hole deep sandbog experience there was a renewed appetite for reconnaissance – every challenging patch of track that could not be overseen from inside the vehicle needed to be scrutinised, whether from the vehicle rooftop vantage point or by footwalking the section. At times, considerable track preparation needed to be done or else risk failure and the consequential very, very difficult extraction or recovery circumstances.

When one travels alone, one needs to take especial care, and that’s how I like it. Len Beadell, arguably the last of the Australian Outback explorers, surveyor and builder, with his Gunbarrel Road Construction Party (GRCP), of many thousands of kilometers of Outback Australian tracks, wrote, when faced with dire circumstances on a solo advance survey, that it would be with the help of the things at the end of his own arms (his own hands) that he would achieve safety and recovery.

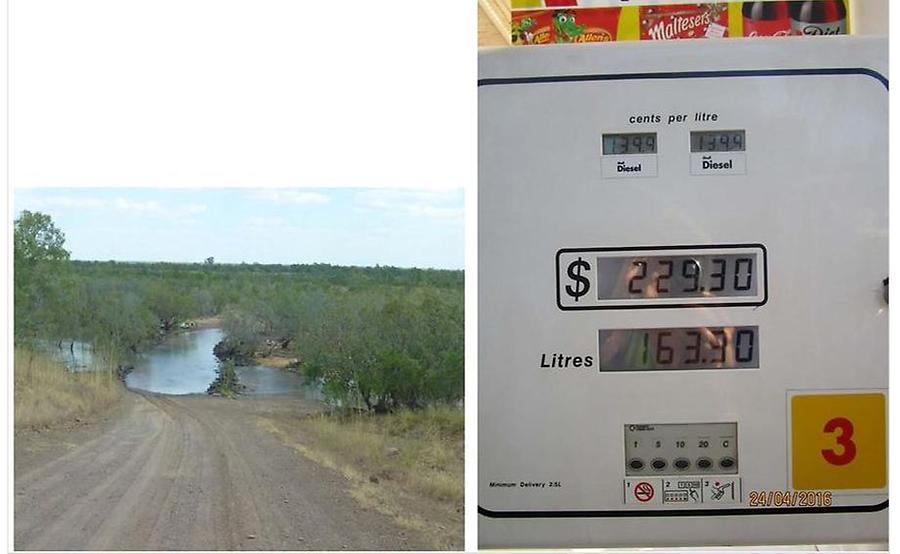

For this trip, one important objective was to get into the Kimberley as soon as practicable after the Wet (the monsoon rains) had abated. So we needed to be flexible, as roads may still be closed due to high water levels and impede our progress. From the Centre, the big town being Alice Springs, we headed northwest along the Tanami Road. I had not yet traversed this route despite having had it on the plan for previous trips. It’s a long ‘short-cut’ from the Centre up into the Kimberley, and quite remote, so fuel management is critical.

As can be seen from the photos, we were using my 1999 model Nissan Patrol 4WD as the as the tow vehicle. It is very robust and reliable, and has been specially prepared for extreme outback conditions through a refurbishment programme. I have boosted the ground clearance, load carrying capacity, fuel tank capacity, and engine power. The vehicle load capacity is now consistent with a constant 600kg in/on the vehicle, plus 200kg down pressure on the tow hitch, in addition to the 220 litres of onboard fuel permitting a traverse of 1100km (220 litres of diesel at say 20litres/100km) without carrying extra fuel in jerry cans (although i have provision to carry up to six 20 litre fuel cans safely). The power boost of the 4.2 litre 6 cylinder engine was accomplished by a larger exhaust system to permit easier breathing to match the much greater quantity of air delivered by a higher capacity turbocharger, and the massive intercooler, the air intake of which can bee seen on the vehicle bonnet in Fig. 11. These changes allow the Nissan Patrol to proceed through rough terrain and tow the 1700kg (maximum loaded mass) with relative ease in areas such as the challenging terrain of the Finke Gorge, and the vast expanse of the Tanami Desert.

A quick note here on diesel as the fuel of choice for outback travel. Firstly, diesel is generally the most available fuel-type as it is used by pastoralists, cattlemen, heavy-haulage operators, and the miners. Secondly, it has a much higher flashpoint (+52 to +96 degrees C) compared to that of petrol (-43 degrees C) making it much safer to store, transfer, and transport, even in harsh and hot outback conditions, and finally, if your fuel management plans have failed you, or you have a need for fuel due to some inadvertent circumstance, then you are much more likely to get help in replenishing your diesel supply from other ‘sensible’ outback travellers who also make more than adequate provision for their journey. In addition to the 220 litres of usable fuel in the Nissan Patrol long-range tanks, I carry 3 x 20-litre canisters of diesel plus an empty spare 20-litre canister on the roofrack in case of emergency need for myself or a fellow traveller – having something to contain the fuel is a precursor for using it!

The human body needs fuel too, especially water, and a supply of this precious liquid when travelling in the Outback is arguably more important than diesel fuel. So, ample supply of both liquids must be on hand – up to 300 litres of diesel, and 240 litres of water makes for a combined mass of 500kg. So much for travelling light! Of course, if one travels in convoy, the resources can be shared, and the total mass of safety and recovery equipment shared across the participant vehicles.

Warnings such as the “last fuel” availability sign need to be heeded – clearly, for an adequately planned trip one is already aware of such conditions, but it is always good to have a double-checking mechanism. In our case we had enough fuel for the Alice Springs to Halls Creek (some 1200km of unknown road conditions) section via the Tanami Road. There was, however, one point where after visiting Wolfe Creek Crater, and with the main vehicle tank approaching empty, I activated the transfer pump to deliver the 70 litres diesel from the auxiliary tank into the main tank for use …. it failed to function! This is where the extra reserve is needed and we reached Halls Creek courtesy of the fuel carried in the canisters.

On one 20-litre canister we can achieve about 100km distance, but Halls Creek was beyond that and thus it was good to have two or three spare canisters. Fuel management is, after personal safety and security, the most urgent issue for attention when in travelling the Outback. At the end of the day, the camping outfit (vehicle, buggy, equipment) provides a self-sufficient, safe and secure base, which can be deployed in just a matter of minutes, for an enjoyable bush camp. Goal achieved.

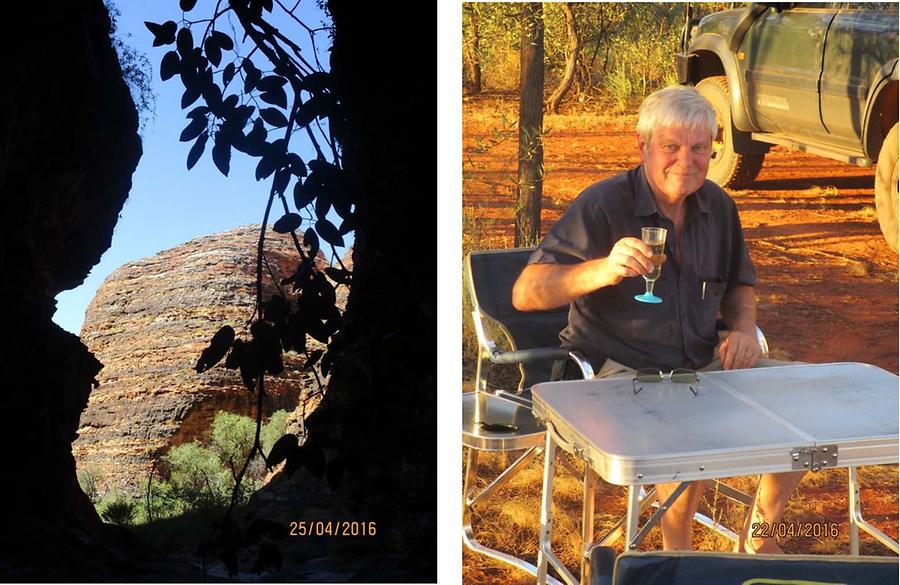

Via the Tanami Road we were transported from Australia’s Centre into the Kimberley region of Western Australia. We re-supplied the essentials in Halls Creek and immediately headed for Purnululu National Park, also known as the “Bungle-Bungles”. It takes considerable effort to get into the area and not surprisingly all vehicles being used here are 4WD. Another option is to fly over the remarkable Bungle-Bungle Range, but that is not what we were doing – Ruth Göttlicher is a walker, and during our visit we completed all the walks that could be done within a one-day per trek timeframe. It was delightfully exhausting! The terrain is spectacular. Unusual, very unusual. The tortuously winding 50km access from the Great Northern Highway to the Ranger Station is called Spring Creek Track and takes a good two hours to traverse. No sooner have you climbed up over the top of one hill, often with the track taking a sharp turn at the crest, you will descend steeply into a gully, possibly water-filled, and then on and up again, having turned many sharp corners in the meantime. I wondered if our ‘creator’ was experimenting with the landscape options before settling on the parameters for a ‘usable’ landscape for citizens to enjoy. Naturally, under these conditions, the hordes of tourists are absent, and one can enjoy nature in relative peace and tranquility, and that’s a primary goal for me. I hope that such conditions can prevail in Australia for some years yet.

Ruth Göttlicher’s log reveals we did six walks during our three-day visit to Purnululu, and we had a most enjoyable and rewarding visit.

A short note on Cane toads (Bufo marinus) – unfortunately we saw many hundreds of these most unwelcome creatures. The area is infested with them, and there seems to be no effective deterrent or control. At my last visit in September 2009 there were none.

Some of the walk tracks were challenging due the unstable and uneven surface, meaning that sturdy boots were essential, but after numerous hours of walking in the rather warm temperatures, and taking in the sights, smells (especially prominent was the flowering spinifex), and sounds, a relaxing camp greeted us upon our return.

As the Wet had been shorter than expected, the East Kimberley visit, that is access from Kununurra and southwest along the Gibb River Road (GRR), was possible. Our main goal now was to be the first visitors for 2016 season at the Mornington Wilderness Camp (MWC). We altered our plans and visited many of the gorges along the GRR in the lead-up to day-1 at MWC -Sunday 1st May 2016.

Crossing the Pentecost River is the first challenge, and as the river levels had receded the water barely lapped the vehicle running boards – that’s how I like it. Coming to grief in such a long water crossing (some 300m), especially in crocodile country, is something most definitely to guard against.

As in all remote regions in Australia, fuel availability is not guaranteed at all times, and is invariably expensive. Sometimes only cash can be used as payment. Mt Barnett was our most expensive per litre fuel purchase to date. The long-range fuel tanks permitted considerable discretion over where and when to access the needed quantity of diesel fuel.

Photo: Ruth Göttlicher and Heinz Dreher

As planned, and with some luck, we arrived at the start of the 90km long track to access MWC at circa 9am, radioed the team at the camp as per established protocol for MWC visitors, and were welcomed a couple of hours later as their first paying guests for 2016.

At MWC we completed five walks, two of which were day-long excursions comprising multiple walking and canoeing activities. Ruth Göttlicher and I had never canoed together, and I am by no means an experienced canoer, my last experience having been to canoe a section of the Snowy River, in the southeast of Australia, downstream of McKillops Bridge with Frank Newton in the early 1970’s. We soon formed into a rowing unison, essential if one wants to make some reasonable progress upstream on the Fitzroy River’s rather long pools as found in Sir John Gorge and Dimond Gorge. The former was undoubtedly our most enjoyable day in the gorges of MWC, and in great part due to the fact that only one canoe, and therefore just two persons, can access the Sir John Gorge on any given day. This makes for a truly wilderness experience as there is just you and nature.

Oh, earlier during our trip we were bogged in deep sand of the Finke River … recall that. Now we also had the experience of being ‘bogged’ on a rock in mid-stream Fitzroy River, with the only option being for one person to go overboard and lighten the boatload – one can guess who that would have been ... yes? The heaviest person! Alas, there are no photos of this as we both needed to carefully concentrate on the ‘un-bogging’ operations.

The MWC experience was most rewarding, and due to the excellent facilities, we could set up a shady camp, and dine out at their restaurant each night, leaving the day entirely free to explore until last light. We didn’t even have to keep our own drinks cool, preferring to leave it all up to the delightful hostesses.

Whilst in the Kimberley the weather had been hotting up, and storms were brewing, just as the Dutchman at Drysdale River Station had foretold a week before. He is a very knowledgeable and an experienced Kimberley resident, and he just ‘felt’ another burst of the Wet was coming.

The day we left MWC there had been overnight rain and we prepared for a very early departure so as to be first on the 90km track north and back to the GRR. Even small amounts of rain can make track sections very soft and boggy as the water collects in hollows and low sections. We had no difficulty but there was plenty of mud being slung about by the tyres. Looking at the forming weather and heeding the Dutchman’s advice we decided to speed up our progress towards Broome.

After MWC we had overnighted at Bell Gorge and were fortunate to be able to get back to the GRR and along it across the Lennard River. There had been some considerable, if steady, rain all night and the track was frightfully slippery for a 5-tonne articulated vehicle to traverse. Again, we left at the crack of first-light so as not to be impeded by vehicles ahead of us or by a track damaged by their attempts at movement, either forwards or backwards – often sideways I fear. The track became so slippery as to be impassable and was closed by mid morning, as we heard from the Ranger at our next intended camp, Windjana Gorge. Even before we had time to stop our vehicle, the Ranger came to advise us that we were welcome, but should we decide to stay, we ought to plan for many days, and even beyond a week! Access to the south and the Great Northern Highway at Fitzroy Crossing was already closed off. With that information we took a nice walk along a short section of the river (Lennard River) and decided to head for Derby, and then Broome, civilization, safety, more options.

Broome had already been drenched in the preceding days, as had been the entire region including the Dampier Peninsula. More rain was on the way. Our overnight camp was in a caravan park with facilities and was a good choice.

Given the looming dark clouds and ongoing inclement weather conditions it was time to head further south, and in this region, first one must proceed east along the Pilbara coast towards Port Hedland. There had been coastal flooding here too in the days prior to our stopover at the Eighty Mile Beach Caravan Park near Wallal Station. There were clear signs of 300mm or 400mm high muddy-watermarks on tents and vehicle tyres.

Having escaped the 2nd-Wet, our next adventure then was to visit the spectacular National Parks of the Pilbara – Millstream-Chichester National Park, and Karijini National Park. The Pilbara is my favourite part of Western Australia, with its rugged rock formations, iron-red colourations, crocodile-free waters, and vast desert regions.

Travel in and around the Pilbara, at least the western parts, as opposed to the eastern desert region, is much easier than in other remote areas of Australia and therefore there are potentially more tourists on the road and occupying campsites. More people means more noise, more rubbish (sadly) and more dust – one needs to be prepared that many travellers deploy little of their cognitive capacity to minimize the affect of their actions on the environment and also on fellow travellers. An extreme example would be the persons in an adjacent campsite using a generator all day and night to run their caravan air-conditioner whether they are in the van or not. But there are more subtle demonstrations too. I counted 64 slams of the car door at one camp just while they were packing up to depart – a matter of 30 minutes. On the H.h list one finds an item dealing with vehicle doors – they just need to be clicked shut, almost silently, until the final positive and complete shutting just prior to eventual departure. I would not recommend leaving the vehicle door open under any circumstance.

After enjoying the water and the walks at Millstream we were en-route to Karijini, when I became increasingly aware of an unwelcome noise in the vehicle. Its source or cause was not obvious but even though we were some 1200km from home in Mahogany Creek I formed the plan that we would head for home, unpack the Nissan Patrol, repack the VW Amarok (another of my 4WD vehicles – and a most comfortable and easy to drive machine indeed), and return to the Plbara to complete our adventure. Of course this was not the original plan, but the decision was clearly correct, as just 250km from home the fifth gear (as I later discovered) in the Nissan Patrol gearbox failed. In the four years since I acquired the 1999 model Nissan Patrol at 140,000km, the prior event of water ingress into the gearbox had not been noticed. Over time, the mixture of oil and water had clearly taken its toll, especially on the hardworking mainshaft spline, and with my newly power and torque boosted engine, 5-tonne total load, and extreme outback terrain, the spline failed. My friend Denis, an exploration-driller expert, with whom I have completed many strenuous physical jobs at both my daughter Naomi’s place and at home in Mahogany Creek over the years, always reminds me to ‘keep the spanners up’ to the machines. Preventive maintenance is needed.

Clearly, noticing such events immediately, and taking consequent action to firstly ensure safety of vehicle occupants and other road users, and secondly to minimize further damage, helped ensure a repair bill of just under $8k, and zero vehicle recovery expense. But that was not our concern just now. We were on a trip in the Pilbara, and were able to proceed home unaided, unpack, repack, and return to Karijini National Park within a week.

Whilst back at home I arranged for a party for some guests, including Gary Burke who plays the ukulele, and also was on the team of musicians that created some of the quintessentially iconic bush music that Ruth Göttlicher enjoyed so much whilst travelling through the very country the lyrics were focused on. Gary is also an academic with special interest in ‘sustainable economics’. A most enjoyable interlude.

Apart from being spectacular for its scenery, the Pilbara is also mining territory, and this requires sharing the roads with some big, very big vehicles.

Gradually our Australian Outback Adventure for 2016 was coming to an end but not before many more walks, including the rather demanding Mt Bruce summit track – without doubt the most challenging track we had undertaken, and arguably, and therefore, the most rewarding.

We also had a delightful evening with the Kirke family in Paraburdoo – three generations of them – my very good friend Doug and his wife Val, daughter Nicole and son Doug, with partners and offspring galore! Just splendid – a most rewarding experience.

Considerable resources must be applied to help ensure the success of longer trips such as the one depicted here. On Ruth Göttlicher’s side she had to come from Austria to Australia and accommodated the measures I had put into place to execute our jointly formed plan. My job was to ensure all equipment and facilities were in top condition – I had spared no expense or effort in this task. Upon our return there was of course a considerable cleanup exercise that Ruth Göttlicher launched into with gusto before her return to Vienna.

Actual ‘cash’ outgoings whilst on tour amounted to just $8000 of which $3500 was for diesel fuel and the remainder for camp fees, meals, food, drinks, and so on. Of course, when planning such trips one needs to keep in reserve considerable resources, as were obviously needed for gearbox repairs, and there are very substantial hidden ‘costs’ (sunk costs in economics-speak) in vehicle acquisition, registration, maintenance, and so on.

The success of a trip cannot be measured in monetary terms (cheap <-> expensive; of course if one does not have the resources to apply then there is ‘no trip’, ipso facto ‘no enjoyment’) but rather, on the ‘feeling’ at the end of each day. There is no doubt that we both enjoyed the easy camping and bush travelling afforded by the camping buggy and other gear, but also the interaction with nature. Invariably, we always had enjoyable camps and campfires, and wonderful walks and respites in nature. So there we have the answer to that question posed by friends “why do you do these things, you know, travel in these remote and uninhabited places?” it’s because I choose to share what nature offers us.

- It was a long-ish trip …and that was the short-ish story about it...hd -